A introdução do Regulamento da União Europeia para Produtos Livres de Desmatamento (EUDR) em 2023 reflete o compromisso da União Europeia (UE) com práticas comerciais sustentáveis no comércio global. No entanto, esse regulamento levanta preocupações para nações parceiras importantes como o Brasil, um grande fornecedor de produtos de madeira para a UE. Usando o setor de madeira nativa do Brasil como um estudo de caso, examinamos as implicações do EUDR na capacidade do país de cumprir com as demandas internacionais de sustentabilidade. Fornecemos uma análise mais detalhada de como os principais critérios do EUDR podem afetar o setor de madeira de florestas naturais do Brasil para a melhor tomada de decisão, preparação e gerenciamento do cenário regulatório. Oportunidades, desafios e lacunas foram apresentados em estruturas abrangentes. Como o novo regulamento será implementado até o final de 2025, colaboração estreita, iniciativas diplomáticas e esforços unificados serão necessários para desenvolver uma estrutura de cooperação que beneficie tanto a produção quanto o comércio sustentável. Será necessário um monitoramento rigoroso dos impactos em evolução do regulamento sobre as exportações de madeira e coprodutos de nações produtoras. Esperamos que nossas descobertas tenham implicações para o setor madeireiro e além.

The European Union (EU) has taken significant measures to address the environmental impact of its global trade with the introduction of the European Union Regulation for Deforestation-Free Products (EUDR) in 2023. The Regulation imposes import restrictions on commodities potentially associated with deforestation and forest degradation. The EU aims to reduce the negative impacts associated with their large-scale consumption (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2023) since the bloc is considered the second largest importer of deforestation and GHG emissions incorporated into the international trade of forest-risk commodities (Wedeux & Schulmeister-Oldenhove 2021).

The EUDR, as well as other initiatives like the UK's Environment Act and the US’s Forest Act (United Kingdon Government 2021; Weiss et al. 2020; U.S Senate 2023) reflects the increasingly stringent sustainability scenario in production and purchasing on trade and environmental regulations. Thus, the Regulation establishes criteria for imports of specific commodities (meat, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soy, rubber, and wood) and prohibits products associated with deforestation and forest degradation after December 31, 2020, from entering the EU market. The three criteria are mandatory and must be met simultaneously: (1) they must be deforestation-free products; (2) produced in compliance to the laws of the exporting country; and (3) subjected to due diligence procedures, including product documentation, risk assessment, and impact mitigation (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2023).

Originally planned to enter into force on 30 December 2024, the EUDR has been postponed to 30 December 2025 for large operators and 30 June 2026 for small and medium-sized enterprises. This postponement was a response by the European Commission to concerns from Member States, third countries and market operators (Council of the European Union 2024).

While signaling the EU's commitment to sustainable trade, the EUDR also raises questions about its implications, particularly for producer countries like Brazil, which maintains a strong relationship with the EU, especially in the agricultural and forestry markets (CNI 2023; Lopes, Chiavari & Segovia 2023). This highlights Brazil’s significant responsibility for the sustainability of its supply chains but also the implications a demand side may have on supply side. In this context, we used the natural forest timber sector in Brazil as a case study of a relevant commodity, given that the EU and the United Kingdom is the second-largest consumer market for timber exported by Brazil (Cesar de Oliveira et al., 2024). We explored the implications of the EUDR for the political and economic scenario of Brazil's natural forest timber sector and considered strategies to mitigate these effects.

Brazil's natural timber supply chain is closely linked to other EUDR-regulated sectors, such as agriculture and livestock, as selective logging often precedes land conversion for these activities (Albert et al. 2023). Demand for timber and agricultural products drives both deforestation and forest degradation (Lapola et al. 2023). Insights from Brazil’s timber sector can inform broader discussions on EUDR challenges and opportunities, supporting early preparedness, risk mitigation, policy evaluation, and market adaptation.

While achieving deforestation-zero trade should be a shared responsibility between consuming and producing nations, the potential implications of deforestation-free policies on countries of production are not fully understood. With Brazilian wood falling into the moderate compliance probability range (Cesar de Oliveira et al. 2024), the country is expected to face difficulties. Early discussions are crucial to anticipate potential ramifications for the natural forest timber trade, particularly associated to the Amazon region, and thereby promote dialogue and informed decision-making among stakeholders.

CHALLENGES

Below we assess the potential implications of the EUDR for Brazil and its native timber sector based on its three main mandatory criteria (see previous section).

Deforestation-free products

The first challenge in demonstrating the “deforestation-free” origin of Brazilian timber stems from the need to establish a consensus on the definition of the term. For the EUDR, deforestation-free means (a) products containing, fed with, or made using commodities produced on land free from deforestation; and (b) specifically for wood-containing products, that the wood has been harvested from the forest without causing forest degradation after the same date (art. 2(13)) (European Parliament & Council of the European Union 2023).

This definition goes beyond the exporting countries’ legislation (Muradian et al. 2025) once it does not differentiate between "legal" and "illegal" deforestation. In the case of Brazil, the Brazilian Forest Code allows varying degrees of vegetation cover suppression on private property and includes provisions for legal deforestation licenses (for sustainable use) from 20% to 80% of the area depending on the Brazilian biome (Brasil 2012).In addition, a legal source of timber in Brazil may be derived from approved deforestation and harvesting licenses in forest areas on rural properties, which may also conflict with the definitions above.

Therefore, a clear distinction between “legal” and “illegal” deforestation could be the starting point for reaching a consensus on the term “deforestation-free” and thus avoid several other associated problems (e.g. conflicts between European and Brazilian legislation). Although divergent notions about what is legal or illegal are common in trade dispute environments (Fakhri 2022),the adoption of terms/concepts that clearly conflicts with the EUDR’s compliance with the “applicable law of the country of production” (next topic) contradicts the EUDR itself. It also raises questions about the imposition of governance and legality standards on economically less privileged countries (Ramcilovic-Suominen & Mustalahti 2022).

The EUDR requires the geolocation of the plots where commodities are produced, and any deforestation or forest degradation sign on the plot automatically disqualifies the commodity or product (European Parliament e Council of the European Union 2023). One of the possible alternatives to prove the legal origin of wood is through supply chain traceability. The traceability of the timber supply chain in Brazil is long and complex, which requires the mandatory National Forest Origin Document, and includes different jurisdictions and traceability systems, which must be unified within the National System for Controlling the Origin of Forest Products (Sinaflor). The system has been improved but is not foolproof and will require continuous adaptations. Moreover, it can be difficult to relate wood co-products to where the wood was harvested or even to distinguish mixtures with wood products of unknown origin. To partly address limitations in Brazilian timber traceability systems (Brancalion et al. 2018; Sotirov et al. 2022; Franca et al. 2023), civil society initiatives (e.g., Timberflow Platform, Unifloresta Legal Verification Program) have been instrumental in enhancing transparency (FAO & WRI 2022). However, it is not clear whether these types of independent non-state governance would be acceptable for compliance with EU standards or even whether voluntary sustainability standards would be part of the EUDR monitoring process. The lack of clarity exposes the risk of restricting Brazilian producers, especially in the Amazon, to a niche market outside the EU (Franca et al. 2023).

Furthermore, an international system capable of accommodating the intricate flows between wood-producing and consuming nations is still missing (Taylor et al. 2020). In this regard, Brazil and the European Union face the challenge of transnational governance to regulate the forest products market.

Compliance with the legislation of the exporting country

Although the EUDR lists compliance with the legislation of the exporting country as a requirement, some clauses of the Regulation conflict with Brazilian environmental legislation either due to the lack of clarity (legal vs illegal deforestation) or due to inconsistencies on specific terms, with potential impacts on the dynamics of Brazilian deforestation. For instance, the EUDR's concept of “forest” follows FAO definition (a minimum of 10% tree cover over an area of 0.5 hectares) (FAO 2025) and, therefore, only the Brazilian Amazon biome would be covered by the EUDR. By restricting the import of commodities from this biome, the EUDR creates a loophole for a potential shift of deforestation from the Amazon to the Brazilian Cerrado (tropical savanna), a biome already under significant deforestation pressure due to agricultural expansion (MapBiomas 2024) and which, according to the criterion adopted by the EUDR, is not considered a “forest.” In this case, national exports of forest-risk commodities (soybeans, meat) may be more affected than the native forest sector, since the pressure for traceability and compliance for zero-deforestation production will be greater for these commodities.

This lack of complementarity between international supply chain policies, such as the EUDR (a trade-based regulation), and national public policies with a territorial approach in producer countries (e.g. land use policy) may undermine the effectiveness of the European Regulation in reducing tropical deforestation at a global level (Muradian et al. 2025; Köthke, Lippe & Elsasser 2023).

Another point is the EUDR’s benchmarking system that ranks countries and regions by import deforestation risk (low-, standard-, and high-risk levels) and may impose severe reputational costs for developing countries like Brazil. The adoption of a criterion that does not consider the diversity of producers (e.g., large and small, legal and illegal) and defines them by purely geographical issues may result in a "collective penalty" for developing countries facing governance issues and punishes even legally operating producers who may face boycotts and bans from importing countries (Sotirov et al. 2022; Karsenty 2023). Brazil has openly expressed concerns about the lack of communication and coordination regarding the EUDR’ benchmarking system (WTO 2023). Along with complaints about competitiveness risks in Asia, Africa and Latin America, the European Commission (EC) has postponed the implementation of this ‘‘benchmarking classification’’ until 2024.

The Brazilian native timber sector can contribute to increasing Brazil's risk rating. Despite Brazil's sophisticated socio-environmental regulations, they have proven insufficient in curbing illegal logging (Brancalion et al. 2018; Garrett et al. 2021), even though Amazon forest concessions have considerably reduced the risk of illegal timber production. To better comply with both domestic and international trade regulations and address deforestation and forest degradation, Brazil needs to enhance its forest governance. Cooperation between the supply and demand sides can help balance the additional costs involved in compliance measures but EUDR does not make explicit any concrete compromise about financial resources to strengthen governance and policies in producing countries (Muradian et al. 2025).

From a political and diplomatic standpoint, this sort of conflict reflects the EU’s unilateral stance, which is seen as conflictual and illegitimate by tropical exporting countries. Brazil, along with other countries, has already sought clarification from the EU on the costs of implementing traceability and due diligence systems and raised concerns about the need to consider different levels of socioeconomic development in the decision-making process (WTO 2023). Generally speaking, countries claim the need to factor in distinct levels of socioeconomic development in EU’s decision-making process. Altogether, potential legal disputes and questioning issues of sovereignty and legitimacy could be raised by Brazil (WTO 2022; Karsenty 2023).

EUDR’s lack of flexibility creates an unnecessary and complex scenario that could undermine efforts to manage the global commons in the long term (van Noordwijk, Leimona & Minang 2025). Recently, the EU launched an initiative to support countries that develop deforestation-free value chains (European Comission 2023). However, a lack of clarity regarding these cooperation measures between producing and consuming countries remains (Berning & Sotirov 2023).The absence of clear mechanisms raises the risk of shifting trade and environmental regulation costs to third countries.

Due Diligence procedures

The adaptation to the due diligence requirements impacts producers, operators, and traders and incurs additional costs, potentially affecting the attractiveness and competitiveness of Brazilian natural forest wood in the European market. For instance, it remains unclear how these costs will be distributed between producers and importers, as due diligence is to be carried out by the importer, who may, in turn, demand evidence from the producer. A high implementation cost may potentially divert Brazilian timber exports to less demanding markets. As highlighted for Brazilian soybean production chain, traders might opt to withdraw from the EU markets or segregate their supply chains (Villoria et al. 2022).Furthermore, heterogeneous interpretation by the EU members of what is acceptable or not in relation to due diligence may discourage market operators from operating in emerging countries (Karsenty 2023).

Currently, China is considered an escape route for forest product exports due to its lack of rules akin to EUDR (Partzsch, Müller & Sacherer 2023). For one, the leakage caused by very strict regulations can be detrimental to achieving the sustainability sought. For another, the diversion of trade flows from the EU to China could foster the so-called “trading down” problem, whereby increasing exports to China - at the expense of exports to countries with higher regulatory standards (such as EU countries) - may undermine the regulations of the exporting region (Adolph, Quince & Prakash 2017). That “trading down” effect needs to be primarily evaluated for Brazilian commodities most exported to China (e.g., soy), which in turn may have direct or indirect impacts on natural forest timber sector.

Another possible outcome for Brazilian wood exports is a reduction in volume and an increase in timber prices, potentially resulting in a decreased overall flow of timber trade (Apeti & N’Doua 2023). This effect has been observed in impact assessments of other EU regulations to curb the trade in illegal timber products (Rougieux & Jonsson 2021).While the share of Brazilian wood exports across different markets may influence the risk of a shift away from EU trade in a near future, it is reasonable to assume a steady trade flow, as Brazilian timber imported into the EU is already governed by the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), unlike other commodities.

Despite recognizing the need for collaboration with smallholders and communities, the EUDR does not specify how this relationship will take place. The impact on small and medium sized Brazilian producers may have been underestimated, as they often lack the resources to meet the stringent requirements of the European Regulation. Smallholders account for 12.6% of the properties producing wood in Brazil (Cesar de Oliveira et al. 2024). Engaging them in the timber production chain or in timber exports can be more costly than disregarding them. This could lead to a segmentation of forest production chains between large and small producers, potentially isolating the latter in unsustainable or illegal domestic markets. It is also likely that large companies operating within forest concessions in the Brazilian Amazon, which typically already access international markets, may gain a competitive edge over those outside the concession system. Evidence on supply chain governance in the commodity sector attests the potential negative externalities and unintended outcomes presented above (Schleifer & Sun 2020; Marx, Depoorter & Vanhaecht 2022). Overall, unequal starting conditions could result in market niches within the timber supply chain

OPPORTUNITIES

Despite the challenges, the EUDR offers opportunities for Brazil's timber sector and, ultimately, international trade. Brazil has already undergone significant forest policy reform, with clear rules for the implementation of sustainable forest management, including timber traceability and remote monitoring systems (Tacconi, Rodrigues & Maryudi 2019; West and Fearnside 2021). However, illegal timber remains a persistent issue throughout the supply chain (Brancalion et al. 2018; Franca et al. 2023).

The EUDR, along with similar regulations, can contribute to the development of transparent tools for tracking supply chains (Parliament & Heflich 2020)by, for example, linking the implementation of the Regulation to jurisdictional or territorial approaches already in place in certain market niches in producer countries (Zabel et al. 2025).Thus, the Brazilian timber sector could benefit from international sustainable trade policies, such as the EUDR, by improving the implementation of its own environmental instruments and policies.

These improvements may require long-term support from consumer countries to achieve greater effectiveness and sustainability (Bager, Persson & dos Reis 2021). This cooperation is needed to both strengthen traceability systems in producer countries and encourage producers to invest in such systems, and thus accelerate anti-deforestation processes and policies (Dürr, Dietz & Börner 2024)

The regulation may also encourage public-private partnerships to reduce deforestation caused by commodity trading, making segregation or desertion of demanding markets no longer an option (Villoria et al. 2022). From another perspective, the adherence of the Brazilian private sector to the EUDR may put pressure on the Brazilian government to improve public traceability systems (Dürr, Dietz & Börner 2024)

As EU’s regulations promote criteria for assuring local socioeconomic development, EU involvement with non-state driven sustainability schemes could help cover a widespread capacity gap in Brazil’s forest law enforcement.

Furthermore, the EUDR binding legal framework could help mitigate the flaws of market-based voluntary mechanisms of compliance and monitoring - reduced in the Brazilian native timber sector - thus contributing to greater efficiency of forest conservation efforts in Brazil (Marx, Depoorter & Vanhaecht 2022).

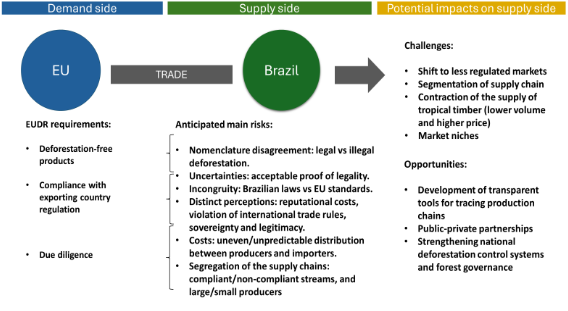

A summary of the main expected risks and major impacts discussed here is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Framework of potential main risks and impacts of the European Union Regulation for Deforestation-Free Products on Brazil's timber sector.

MOVING FORWARD

The EU's significant global market influence stems from what is known as the Brussels Effect - the EU's capability to globally disseminate its unilateral high market standards (Bradford 2012). The Brussels Effect suggests that the EU's regulatory standards often become de facto global standards as companies around the world adopt them to access the lucrative EU market. The Brussels Effect, embodied in the EUDR, with its stringent criteria for deforestation-free products and due diligence procedures, is likely to have a broad impact beyond the EU's borders, influencing global trade dynamics and forestry practices. Adherence to EUDR standards can lead to enhanced forest governance, transparency, and sustainable practices. On the other hand, the challenges associated with meeting these standards, such as the need for costly traceability systems, may disproportionately affect smaller producers and countries with fewer resources. The EUDR thus underscores the complex interplay between transnational regulations, market dynamics, and the sustainability efforts of producing nations.

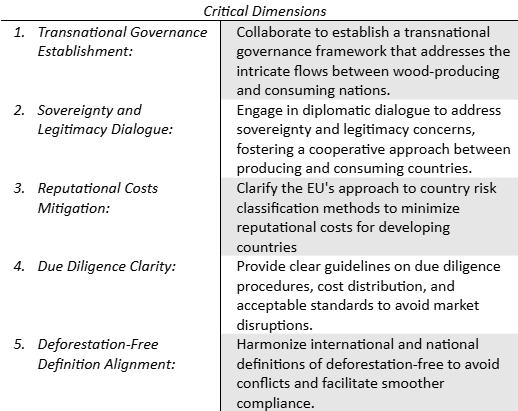

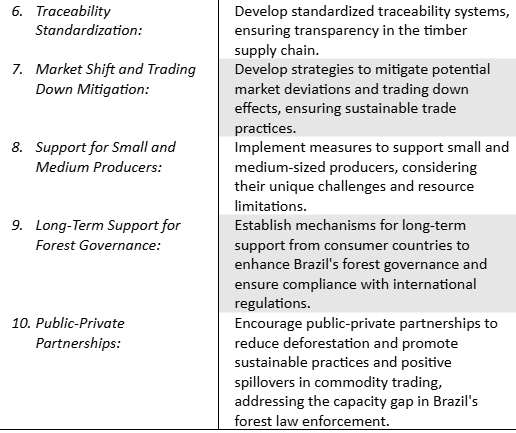

Reflecting on the potential political and economic impacts of EUDR on the Brazilian timber sector reveals remaining challenges along with suggested paths for progress (Table 1). Addressing these challenges requires a blend of political and technical solutions, underscoring the need for flexibility, dialogue, and shared commitment. Overcoming these challenges not only safeguards sustainable international trade but also ensures mutual benefits for all parties involved.

Table 1: Critical dimensions for advancing sustainable EU-Brazil timber trade based on EUDR implications.

Among the listed challenges, some are more straightforward than others. The potential role of public-private partnerships concerning private certifications, for instance, needs further consideration. The EUDR has raised legitimacy questioning from developing countries since its onset and the role of private certifications can either exacerbate or mitigate that hesitation. According to the EUDR, “certification or other third-party verified systems” could be a complementary means of assessing the risk of imported products. Engaging with private rule-makers via public-private partnerships helps reach further stakeholders and mitigate capacity gaps, thus improving legitimacy (Faude & Groβe-Kreul 2020). However, it is not clear if engaging with voluntary certifications generate positive spillovers which are required for a holistic approach to sustainability (Heilmayr, Carlson & Benedict 2020).

In the case of Brazilian timber, the output is likely to face hurdles. Most of the certified areas occur in planted forests (Sanquetta, Mildemberg, and Sella Marques Dias 2022).The percentage of voluntary certification in native forest areas represents only 2% of the total harvested area (Cesar de Oliveira et al. 2024).Therefore, for Brazil, forest certification (leveraged by the EUDR) would be a long-term strategy (Rana and Sills 2024).As the Brussels Effect takes form, it is likely that the volume of certified timber will increase consistently over the years. In any case, certification schemes must be kept voluntary. In some cases, regulations or public-private agreements, such as forest concessions in Brazil, can ensure sustainability and legality without imposing additional costs on producers for forest certification. Clear and transparent standards of legality and/or sustainability may be sufficient to ensure compliance within due diligence processes. That decision is not trivial, since the EU Commission encounters various perspectives, including lobbying efforts from private certifications seeking recognition of their standards within due diligence systems (Renckens, Pue & Janzwood 2022)

CONCLUSION

Particularly in Brazil, EUDR’s potential effects on natural forest timber exports encompass legal, political, economic, and socio-environmental considerations. These findings help drawing some broad lessons that can be also assessed for other commodities, and for Brazil and the EU. For instance, the main challenges and opportunities listed in our figure 1 can be extended to other Brazilian commodities. The EU's unilateral stance and persisting uncertainties in Brazil regarding the regulation's operation and international cooperation may reinforce political and leakage risks, potentially result in shifts in timber exports and segmented forest production chains in Brazil.

On the supply side, Brazil already has robust forest monitoring mechanisms and should take advantage of the EUDR to strengthen national tools and policies to combat deforestation and enhance forest management. Brazilian native timber exports to the EU, which already operated under the influence of the previous EU regulation to combat timber illegality, the EUTR, may have implications under the new regulation (EUDR) as discussed here. This means that other Brazilian commodities exporting to the EU, that were not under previous regulation, may need time to adapt to the required criteria. The involvement of political, private and civil society actors in a collective effort to promote supply chains free from illegality and guided by sustainability will be also crucial in this path.

As a global issue, efforts towards sustainability must start from the dynamic interaction between the supply and demand sides. To ensure balanced, prompt, and enduring solutions, diplomatic dialogue, international cooperation, and efforts from both sides are key in promoting sustainable production chains. Positive incentives for exporters and importers can contribute more to fair and sustainable trade than relying on bans and sanctions.

The EUDR represents a commendable step toward responsible global trade. However, significant doubts remain, along with a pressing need for clearer implementation measures both within the European Union and, most notably, in producing countries. Not by chance, less than three months before the planned enforcement date (December 2024), the European Commission decided to postpone EUDR implementation to 2025 (large companies) or 2006 (small/medium-sized enterprises) (Council of the European Union 2024), ensuring more time for adaptations within and outside the EU. This was a positive sign that the EU is listening to affected parties and can also address gaps in the EUDR while production countries and operators adapt to the new requirements.

Finally, the implications assessed here of the effects of the EUDR on Brazilian exports of timber (and co-products) allow for the anticipation of mitigating measures but a closely monitoring when the EU regulation comes into force is both desirable and necessary.

Acknowledgements

The first author was partly supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) (funding code 001). We thank Metodi Sotirov, Paulo Moutinho and Olívia Zerbini Benin for valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

References

Adolph, Christopher, Vanessa Quince & Aseem Prakash. 2017. “The Shanghai Effect: Do Exports to China Affect Labor Practices in Africa?” World Development 89 (January):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.05.009.

Albert, James S., Ana C. Carnaval, Suzette G.A. Flantua, Lúcia G. Lohmann, Camila C. Ribas, Douglas Riff, Juan D. Carrillo, et al. 2023. “Human Impacts Outpace Natural Processes in the Amazon.” Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo5003.

Apeti, Ablam Estel & Bossoma Doriane N’Doua. 2023. “The Impact of Timber Regulations on Timber and Timber Product Trade.” Ecological Economics 213 (July): 107943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107943.

Bager, Simon L, U Martin Persson & Tiago N.P. dos Reis. 2021. “Eighty-Six EU Policy Options for Reducing Imported Deforestation.” One Earth 4 (2): 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.011.

Berning, Laila & Metodi Sotirov. 2023. “Hardening Corporate Accountability in Commodity Supply Chains under the European Union Deforestation Regulation.” Regulation & Governance 17 (4): 870–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12540.

Bradford, Anu. 2012. “The Brussels Effect.” Northwestern University Law Review, Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper n 533, 107 (1). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2770634.

Brancalion, Pedro H. S., Danilo R. A. de Almeida, Edson Vidal, Paulo G. Molin, Vanessa E. Sontag, Saulo E. X. F. Souza & Mark D. Schulze. 2018. “Fake Legal Logging in the Brazilian Amazon.” Science Advances 4 (8). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat1192.

Brasil. 2012. Lei No 12.651. Dispõe Sobre a Proteção Da Vegetação Nativa; Altera as Leis Nos 6.938, de 31 de Agosto de 1981, 9.393, de 19 de Dezembro de 1996, e 11.428, de 22 de Dezembro de 2006; Revoga as Leis Nos 4.771, de 15 de Setembro de 1965, e 7.754, de 14 de Abril de 1989, e a Medida Provisória No 2.166-67, de 24 de Agosto de 2001; e Dá Outras Providências. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União.

Cesar de Oliveira, Susan E.M., Louise Nakagawa, Gabriela Russo Lopes, Jaqueline C. Visentin, Matheus Couto, Daniel E. Silva, Francisco d’Albertas, Bruna F. Pavani, Rafael Loyola & Chris West. 2024. “The European Union and United Kingdom’s Deforestation-Free Supply Chains Regulations: Implications for Brazil.” Ecological Economics 217 (March). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.108053.

CNI, Confederação Nacional da Indústria. 2023. “Regulamento Da União Europeia Condiciona Importação de Determinadas Commodities Agrícolas e Seus Derivados a Due Diligence de Desmatamento.” Análise de Política Comercial, 2023. https://www.portaldaindustria.com.br/publicacoes/2023/7/analise-de-politica-comercial-10-regulamento-da-uniao-europeia-condiciona-importacao-de-determinados-commodities-agricolas-e-seus-derivados-due-diligence-de-desmatamento/#:~:text=Em junho de 2023%2C.

Council of the European Union. 2024. “EU Deforestation Law: Council Formally Adopts Its One-Year Postponement.” December 18, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/12/18/eu-deforestation-law-council-formally-adopts-its-one-year-postponement/.

Dürr, Jochen, Thomas Dietz & Jan Börner. 2024. “Telecoupling of Governance Systems Under the Eudr: Scenarios for the Brazilian Beef and Soy Value Chains.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4847389.

European Parliament, and Council of the European Union. 2023. “Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the Making Available on the Union Market and the Export from the Union of Certain Commodities and Products Associated with Deforestation and Forest Degradation and repealing Regulation.” Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R1115&qid=1687867231461.

Fakhri, Michael. 2022. “Markets, Sovereignty, and Racialization.” Journal of International Economic Law 25 (2): 242–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgac021.

FAO. 2025. “FAO Global Forest Resources Assessments - Terms and Definitions.” 194. Rome.

FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and WRI - World Resources Institute. 2022. Timber Traceability – A Management Tool for Governments. FAO; World Resources Institute (WRI). https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8909en.

Faude, Benjamin & Felix Groβe-Kreul. 2020. “Let’s Justify! How Regime Complexes Enhance the Normative Legitimacy of Global Governance.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (2): 431–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa024.

Franca, Caroline S. S., U. Martin Persson, Tomás Carvalho & Marco Lentini. 2023. “Quantifying Timber Illegality Risk in the Brazilian Forest Frontier.” Nature Sustainability, July. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01189-3.

Garrett, Rachael, Frederico Cammelli, Joice Ferreira, Samuel Levy, Judson Valentim & Ima Vieira. 2021. “Forests and Sustainable Development in the Brazilian Amazon_ History, Trends, and Future Prospects.” Annual Review Of Environment and Resources 46:625–52.

Heilmayr, Robert, Kimberly M. Carlson & Jason Jon Benedict. 2020. “Deforestation Spillovers from Oil Palm Sustainability Certification.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (7): 075002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab7f0c.

Karsenty, Alain. 2023. “Europe’ s Regulation of Imported Deforestation : The Limits of an Undifferentiated Approach.” ITTO Tropical Forest Update, 2023. https://www.itto.int/tfu/2022/12/28/sustainable_tropical_forestry_a_pathway_to_a_healthy_planet/.

Köthke, Margret, Melvin Lippe & Peter Elsasser. 2023. “Comparing the Former EUTR and Upcoming EUDR: Some Implications for Private Sector and Authorities.” Forest Policy and Economics 157 (995): 103079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103079.

Lapola, David M., Patricia Pinho, Jos Barlow, Luiz E.O.C. Aragão, Erika Berenguer, Rachel Carmenta, Hannah M. Liddy, et al. 2023. “The Drivers and Impacts of Amazon Forest Degradation.” Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abp8622.

Lopes, Cristina Leme, Joana Chiavari & Maria Eduarda Segovia. 2023. “Brazilian Environmental Policies and the New European Union Regulation for Deforestation-Free Products: Opportunities and Challenges.” Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/brazilian-environmental-policies-and-the-new-european-union-regulation-for-deforestation-free-products-opportunities-and-challenges/.

MapBiomas. 2024. “RAD2023: Relatório Anual Do Desmatamento No Brasil 2023.” São Paulo. https://alerta.mapbiomas.org/.

Marx, Axel, Charline Depoorter & Ruth Vanhaecht. 2022. “Voluntary Sustainability Standards: State of the Art and Future Research.” Standards 2 (1): 14–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards2010002.

Muradian, Roldan, Raras Cahyafitri, Tomaso Ferrando, Carolina Grottera, Luiz Jardim-Wanderley, Torsten Krause, Nanang I. Kurniawan, et al. 2025. “Will the EU Deforestation-Free Products Regulation (EUDR) Reduce Tropical Forest Loss? Insights from Three Producer Countries.” Ecological Economics 227 (January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108389.

Parliament, European & Aleksandra Heflich. 2020. “An EU Legal Framework to Halt and Reverse EU-Driven Global Deforestation.” European Parliamentary Research Service - EPRS.

Partzsch, Lena, Lukas Maximilian Müller & Anne-Kathrin Sacherer. 2023. “Can Supply Chain Laws Prevent Deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Indonesia?” Forest Policy and Economics 148 (April 2022): 102903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2022.102903.

Ramcilovic-Suominen, Sabaheta & Irmeli Mustalahti. 2022. “Village Forestry under Donor-Driven Forestry Interventions in Laos.” In Routledge Handbook of Community Forestry, 434–48. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367488710-33.

Rana, Pushpendra & Erin O. Sills. 2024. “Inviting Oversight: Effects of Forest Certification on Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.” World Development 173 (October 2023): 106418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106418.

Renckens, Stefan, Kristen Pue & Amy Janzwood. 2022. “Transnational Private Environmental Rule Makers as Interest Organizations: Evidence from the European Union.” Global Environmental Politics 22 (3): 136–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00665.

Rougieux, Paul & Ragnar Jonsson. 2021. “Impacts of the FLEGT Action Plan and the EU Timber Regulation on EU Trade in Timber Product.” Sustainability 13 (11): 6030. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116030.

Sanquetta, Carlos Roberto, Celine Mildemberg & Leticia Maria Sella Marques Dias. 2022. “NÚMEROS ATUAIS DA CERTIFICAÇÃO FLORESTAL NO BRASIL.” BIOFIX Scientific Journal 7 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.5380/biofix.v7i1.81042.

Schleifer, Philip & Yixian Sun. 2020. “Reviewing the Impact of Sustainability Certification on Food Security in Developing Countries.” Global Food Security 24 (February 2019): 100337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100337.

Sotirov, Metodi, Claudia Azevedo-Ramos, Ludmila Rattis & Laila Berning. 2022. “Policy Options to Regulate Timber and Agricultural Supply-Chains for Legality and Sustainability: The Case of the EU and Brazil.” Forest Policy and Economics 144 (July): 102818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2022.102818.

Tacconi, Luca, Rafael J. Rodrigues & Ahmad Maryudi. 2019. “Law Enforcement and Deforestation: Lessons for Indonesia from Brazil.” Forest Policy and Economics 108 (September 2018): 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2019.05.029.

Taylor, R., C. Davis, J. Brandt, M. Parker, T. Stäuble & Z. Said. 2020. “The Rise of Big Data and Supporting Technologies in Keeping Watch on the World’s Forests.” International Forestry Review 22 (1): 129–41. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554820829523880.

United Kingdon Government. 2021. “Environment Act 2021.” 2021. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/30/contents.

U.S Senate. 2023. “S. 3371 - FOREST Act of 2023.” 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/3371/text.

Villoria, Nelson, Rachael Garrett, Florian Gollnow & Kimberly Carlson. 2022. “Leakage Does Not Fully Offset Soy Supply-Chain Efforts to Reduce Deforestation in Brazil.” Nature Communications 13 (1): 5476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33213-z.

Wedeux, Béatrice & Anke Schulmeister-Oldenhove. 2021. “Stepping up? The Continuing Impact of EU Consumption on Nature Worldwide.” WWF. https://www.wwf.eu/?2965416/Stepping-up-The-continuing-impact-of-EU- consumption-on-nature.

Weiss, Jeffrey, Katy Shin, Eva Monard, Simon Tilling & Byron Maniatis. 2020. “Comparing Recent Deforestation Measures of the United States , European Union , and United Kingdom.” Environmental Law and Management 32 (3): 91–94. https://doi.org/https://www.lawtext.com/publication/environmental-law-and-management/contents/volume-32/issue-3.

West, Thales A.P. & Philip M. Fearnside. 2021. “Brazil’s Conservation Reform and the Reduction of Deforestation in Amazonia.” Land Use Policy 100 (May 2019): 105072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105072.

WTO, World Trade Organization. 2023. “European Union Regulation on Deforestation and Forest Degradation-Free Supply Chains: Communication from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru.” https://doi.org/https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/CTE/GEN33.pdf&Open=True.

WTO, World Trade Organization -. 2022. “Joint Letter: European Union Proposal for a Regulation on Deforestation-Free Products.” World Trade Organization. https://doi.org/https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/G/AG/GEN213.pdf&Open=True.

Zabel, Astrid, Lydia Afriyie-Kraft, Marie Louise Avana-Tientcheu, Amare Bantider, Thomas Breu, Elisabeth Bürgi Bonanomi, Sandra Eckert, et al. 2025. “Time for Change: Recommendations for Action during the Proposed EUDR Postponement.” Ambio, January. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-024-02127-z.